Preparing the Neck and Shoulders for Deep

Work, Part II

Myofascial Techniques for the Superficial

Fascia

©

2008, Til Luchau, Advanced-Trainings.com

Part II: Releasing Superficial

Restrictions

Once youÕve seen or felt where your clientÕs outer layers

are tugging or creeping along with head and neck movement, you can go to work.

A word about sequencing your superficial work on the upper torso: in most

cases, youÕll begin by releasing the posterior restrictions of the upper back,

and end by working the anterior restrictions. This is the order weÕre using in

this article. Why this back-to-front progression? Since most of us tend to have

our heads forward of the coronal midline, and be narrower across the front of

our chest than across our upper back, the anterior fascial layers of the chest

and shoulders tend to be shorter than the posterior layers of the shoulders and

back. Ending by lengthening the shorter anterior restrictions balances the

earlier work on the posterior side, and leaves the client with a greater sense

of anterior width, length, and freedom, and so helps with overall alignment. A

possible exception to this ordering: if your client has a very flat upper

thoracic curve, you may want to reverse the sequence, and end with work on the

back to encourage more spinal flexion.

1. Technique: Over the Edge

Ask your client to lie face down on your table, arms at the

sides, with his or her head and neck just over the top edge of the table. The

edge of the table should fall an inch or two below the top of the sternum. Your

client may need to adjust upwards or downwards a bit so that the edge is

comfortable. You wonÕt want to leave your client like this too long, but youÕll

usually have at least two or three minutes to work before his or her head

starts to feel too full.

Once your client is comfortable, ask him or her to turn the

head from side-to-side as you again watch or feel the outer tissue layers, in

order to re-check your findings. Look again at the up-and-down movements too,

again using care to avoid any neck compression with extension. Often, this

prone position will make the superficial restrictions even more obvious.

The tool weÕll use to release these restrictions is the flat

of our forearm; specifically, the first few inches of the ulna just distal to

the elbow. Use this tool to gently anchor the inferior margins of the places

you saw or felt superficial restrictions. We donÕt use oil or cream, as weÕll

be using friction more than pressure to contact the layer we want to release.

Also, we wonÕt be sliding much—our client will provide the movement

needed for release.

Once you have the outer layers gently anchored with your forearm, ask your client to slowly turn his or her head away from the side youÕre working. Feel for a direction of your pressure that gently lengthens the superficial layers being pulled by the head movement. Imagine that youÕre helping your client lengthen and free herself inside the wetsuit-like outer layers of superficial fascia.

Figure 1: The

"Over-the-Edge" technique. Although relatively safe, head-down

positions are usually contraindicated for clients with uncontrolled high blood

pressure, a history or risk of stokes, vertigo, or acute sinus issues.

Alternatively, you can ask your client to lift and lower the

head (extend and flex the spine) as you lengthen the layers of the back

inferiorly. YouÕll find that most release will happen on the eccentric phase of

the motion, that is, while your client is lowering his or her head.

Remember, your client will get uncomfortable you leave them

in this position for more than a few minutes. Although relatively safe,

head-down positions are probably contraindicated for clients with uncontrolled

high blood pressure, a history or risk of stokes, vertigo, or acute sinus

issues.

2. Technique: Lateral Core/Sleeve

Differentiation

After releasing the posterior restrictions of the back and shouldersÕ superficial layers, youÕll want to broaden and continue this release by addressing restrictions in the lateral and posterior neck.

The tool weÕll use is the soft fist: rather than a hard, closed fist, the soft fist is open, easy and relaxed, with both the fingers and thumb out and relaxed (Figure 2: Lateral Core/Sleeve Differentiation. Gently use a soft, open hand to ease the outer layers of the neck posteriorly. Do not put any pressure on the underlying structures of the throat and lateral neck—the Styloid Process, Carotid Artery, and Vagus Nerve are all in this region and merit special care.). It is important to keep the wrist and metacarpals aligned with the forearm—this will both protect your wrist from strain or compression, and allow you to work less, and so make your touch more sensitive.

Using the proximal knuckles of your soft fist, catch the outer layers of the neck, just anterior and superficial to the SCMÕs belly. By gently moving these outer layers posteriorly, you can take up any slack in the outer wrappings of the neck. There are delicate structures in the neck, so be sure youÕre staying superficial. Think about just catching the outer collar of a turtleneck sweater (the superficial fascia), without putting any pressure on the deeper structures, or pulling the ÒcollarÓ to tightly across the front of the throat. Your client should be comfortable—if he or she feels that youÕre pressing too hard on neck structures or pulling too much on the front of the throat, readjust your pressure, layer, and direction until there is not discomfort.

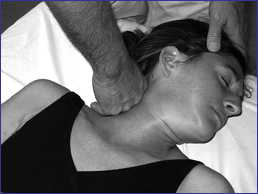

Figure 2: Lateral Core/Sleeve Differentiation. Gently

use a soft, open hand to ease the outer layers of the neck posteriorly. Do not

put any pressure on the underlying structures of the throat and lateral

neck—the Styloid Process, Carotid Artery, and Vagus Nerve are all in this

region and merit special care.

Once youÕve gently anchored and taken up the slack in the outer layers of the lateral neck, ask your client to gently turn his or her head away from the side youÕre working. Your working hand stays static, and so any sliding is initiated by the clientÕs movement and tissue release. Make sure your clientÕs movement is slow and focused—Òmuscling throughÓ the movement wonÕt help him or her learn an easier way of moving, and might even cause you both to miss the cues that keep your pressure safe. You can repeat this anchoring and turning in two or three places between the base of the neck and the base of the skull; and then on the opposite side.

This technique can also serve as a great finishing move: Ida

Rolf (the originator or Rolfing¨ structural integration) often used this

technique to make sure the neck was adaptable, long, and free at the end of his

or her sessions.

In Part III of this article, we'll look at a way to release the anterior

aspect of the neck and shoulder girdle.

Look for it in the next newsletter from Advanced-Trainings.com