The Thinking Practitioner Podcast

w/ Til Luchau & Whitney Lowe

Episode 48: Psoas Work: Is it Safe? Is it Necessary?

(Hip Jam Rebroadcast)

Handout | Transcript | Subscribe | Comments | ⭑⭑⭑⭑⭑

Or, listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher or Google Play.

In honor of the upcoming Hip Jam, Whitney and Til discuss the controversies, disagreements, considerations, and their own views on the infamous psoas muscle in manual therapy and massage in this "Greatest Hits" rebroadcast of ep25. Download the handout with detailed episode notes, techniques and tests, and a special chapter from Til’s book from http://a-t.tv/ttp-psoas/, plus check out the Hip Jam.

Topics include:

- Psoas: Holy Grail muscle, or wholly irrelevant?

- Psoas and back pain, leg length, etc.;

- Safety considerations;

- What Til and Whitney actually do (and don’t do) in practice.

Resources and references discussed in this episode:

- Free Episode Handout with extras

- Book: Yoga Biomechanics (Mitchell 2018)

- Blog: ‘Psoas, So What’ (Ingraham 2015)

- Study: Psoas and lumbar disability (Wagner et al 2018)

- Video: Whitney Lowe demonstrates a modified Thomas test

- Video: Til Luchau demonstrates a hands-on psoas technique

- Whitney Lowe’s site: AcademyOfClinicalMassage.com

- Til Luchau’s site: advanced-trainings.com

Episode image copyright Primal Pictures, used by permission

Sponsor Offers:

- The Hip Jam: bit.ly/Hip-Jam-TTP

- Books of Discovery: save 15% by entering "thinking" at checkout on booksofdiscovery.com.

- ABMP: save $24 on new membership at abmp.com/thinking.

- Handspring Publishing: save 20% by entering “TTP” at checkout at handspringpublishing.com.

About Whitney Lowe | About Til Luchau | Email Us: info@thethinkingpractitioner.com

(The Thinking Practitioner Podcast is intended for professional practitioners of manual and movement therapies: bodywork, massage therapy, structural integration, chiropractic, myofascial and myotherapy, orthopedic, sports massage, physical therapy, osteopathy, yoga, strength and conditioning, and similar professions. It is not medical or treatment advice.)

Full Transcript (click me!)

Til Luchau:

Hi, this is Til Luchau. There are very few muscles that have as much mystery or controversy as the psoas. For this episode, Whitney and I are re-sharing one of our most popular episodes from last year, entitled Psoas Work: Is it Safe? Is it Necessary? Be sure to download the handout, and enjoy the conversation

Whitney Lowe:

Thanks, Til. And I'm Whitney Lowe. Handspring has a new instructional webinar series called Moved to Learn! It's a regular series, each of 45-minute segments featuring some of their amazing authors, including a recent one from Til. So head on over to their website at handspringpublishing.com to check those out. And be sure to use the code TTP at checkout for a discount. Thanks Handspring for supporting the podcast. So hey, Til. How's it going? We were on a little bit of a hiatus here from our recording. It's good to be back doing this once again.

Til Luchau:

Good to be back with you, Whitney. We had an episode off, and that's always good. I have an idea for today. I thought we could take turns muting the mic so just one of us at a time has a mic. What do you think?

Whitney Lowe:

Or maybe give somebody else control to be able to mute us at their own whim, or something like that. I think we behave pretty well here, so we can probably do okay without our mic being muted.

Til Luchau:

We'll give it a try.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

You had some interesting questions, though. Why don't we talk about the psoas, yeah?

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. I thought we've had a number of people ask for this, and this has been one of our hotly requested topics, so I thought, "Hey, it's about time. Let's do this psoas we don't go on any longer without addressing it."

Til Luchau:

Oh, boy. Okay, the jokes have started already. So you proposed this because it had been requested. Any other reason? You want to talk about the psoas?

Whitney Lowe:

Well, yeah. I think it's a somewhat controversial topic, and there's a lot of rich stuff to dive into here. So I thought this would be great, and I know you've worked a lot in this region, and I know especially with your background in structural integration work, there's a lot of emphasis on this. I've seen it a lot in the world of orthopedics and the stuff that I've been doing, and I think I would like to sort of see and share some of our perspectives of where current thinking is with everybody about this.

Til Luchau:

Yeah. I appreciated you bringing it up, and I look forward to hearing what you have to say. I should mentioned at this point, listeners, if you want, you can download a handout that has a brief outline of our points we're talking about today, and then some extra material. I'll give the link down... It's also on the podcast description and on Whitney's side and my side. But the link is a-t.tv/ttp-psoas/. So that's a-t.tv/ttp-psoas/ for the free handout that will kind of outline what we're talking about today.

Whitney Lowe:

Sounds good. All right. So in terms of starting here, I'm just curious your thoughts about this. If you look in the world of massage, bodywork and manual therapy, lot of the readings, the talkings, the discussions, there is all this mystique and mystery surrounding the psoas. It seems to be kind of a muscle of intense fascination for so many people. And I'm kind of curious, why do you think that is? What's with the psoas? What's the big deal here?

Til Luchau:

Well, okay. I'll give you my opinion. I want to hear yours, of course. "But why the fascination with the psoas?", you said in your little notes here. "Why is it the holy grail muscle?" I like that. Ida Rolf gave it a lot of importance in her structural model. She really felt like it had an important role in lumbar lengthening, you could say, especially. There's some specific reasons maybe to the structural integration approach, but I think why in manual therapy in general and massage therapy, maybe it's because it's so deep. Some people say, "It's the deepest muscle." Maybe that would represent some sort of acme of achievement if you can work on the deepest possible muscle. Maybe because it can be, and classically, there's some pretty intense psoas work. It's kind of rite of passage in a lot of ways. I don't know. What do you think?

Whitney Lowe:

I am in agreement with you, there. And I think it's kind of interesting. I see this as a place where perhaps some different things converge where the biomechanical model... So for example, those that are really oriented toward a complex mechanistic sort of view of the way the body functions. The psoas is a complex and challenging muscle in that realm. Also, like you said, for those that view the body more from a sort of holistic or even spiritual aspect, the fact that it's deep and mysterious and does all this other stuff makes it sort of this muscle of mystery. So it's kind of like something that everybody can point to as having a great degree of pertinent focus or interest maybe.

Til Luchau:

No, you're right. There is some sort of mystical dimension to it, at least in some models. Ida Rolf probably had some of that around that. But Liz Koch also has called it, "The muscle of the soul," and has done a lot of writing around how important it is. It has some key roles in some trauma therapies, a body's been through trauma therapy where it's thought to be one of the deepest core structures that react to trauma in that model. I don't know if those are evidence-based or more just narratives that people are using therapeutically, but it does seem to have a special role in that sense.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Yeah. I think so. And so for us as manual therapists, I think there's a lot of... This is another one of those places. I saw this a great deal when I was teaching at entry level massage training programs, and also, in continuing education workshops, lots of people coming to this area, feeling a great deal of trepidation and uncertainty about what they're doing here. And I think the difficulty of... For example, because it is such a deep muscle, it's difficult to access, and there are a number of sensitive structures around it, which we'll get to in a little bit, talking about that in some more detail, makes it harder or more challenging for people to feel confident and comfortable in what they're doing. So I think that's probably been one of the other things that's added a lot of sort of mystique and trepidation around dealing with it for a lot of folks.

Til Luchau:

Yeah. It's in the belly, too, for goodness sake. It's behind your belly. It's like a sensitive area there.

Whitney Lowe:

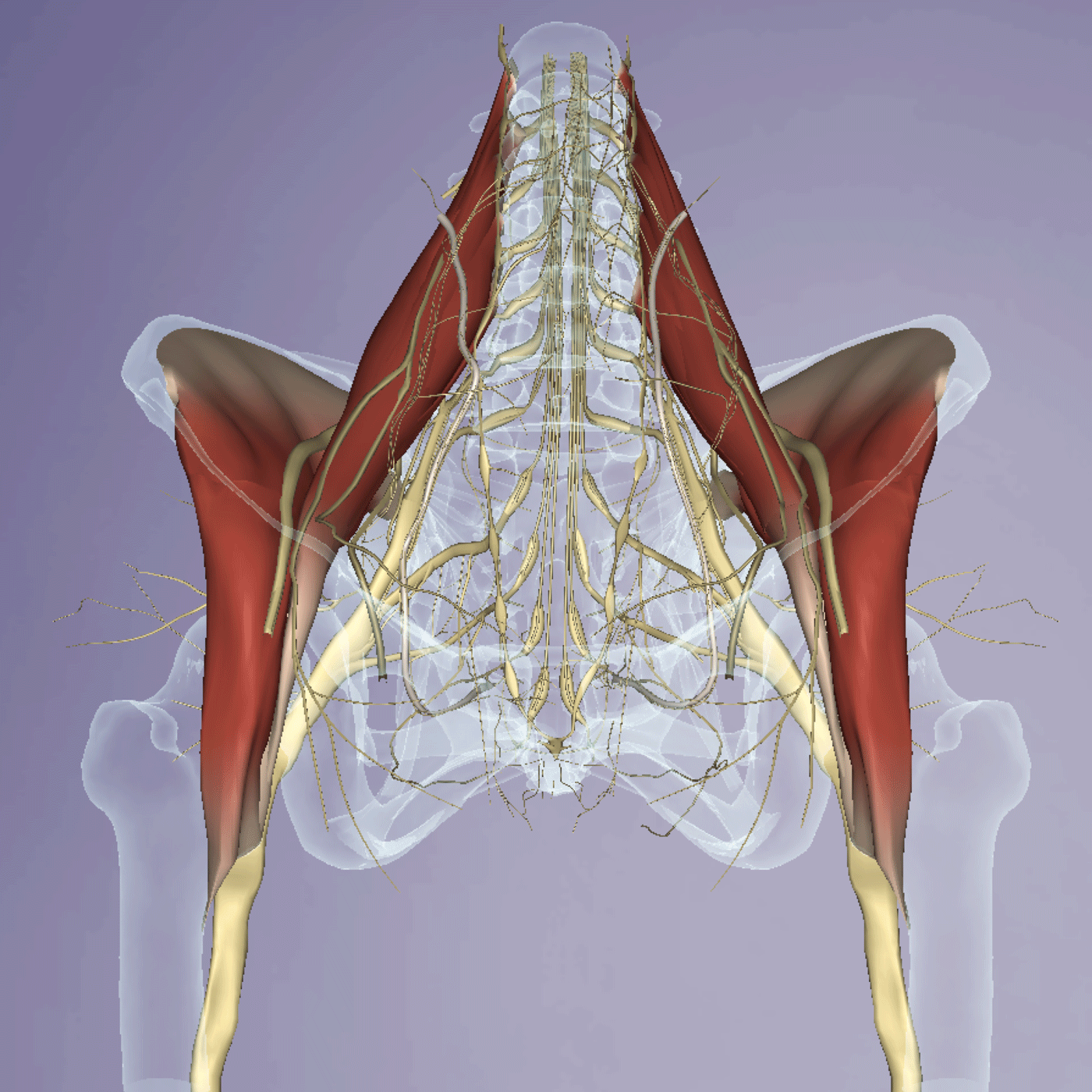

Right. Yeah. So yeah. So let's explore that in a little bit more detail. So just again, just so we sort of lay some groundwork here, I think it might be beneficial to remind people what we're talking about with the iliopsoas being really a muscle of two component parts, the psoas major and the iliacus, coming together and sharing distal attachment side. So the psoas major coming off of the lumbar vertebra, and the iliacus coming off of the inside of the pelvic bowl. And then the two blending together and attaching on the lesser trochanter of the femur in their distal attachment. But I think when we talk about psoas work, most people are probably referring to psoas major. Would you agree that that's what most people focus on there?

Til Luchau:

Yeah. That's right. It's the lumbar portion of that complex, you could say. Which I guess that about half of people includes the psoas minor, if you really want to get nerdy about the whole thing. But yeah, that's great. That's a great reminder. And it's essentially on the sides and front of the lumbar bodies. And so that's the place that you're talking is behind the belly.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Right. And so for us even looking at it, I want to talk a little bit about some of the things that we hear about the psoas in terms of why we should work on it. For example, some of that has to do with its role in certain things. It's often given a great deal of importance in things like pelvic alignments, anterior pelvic tilts, or some other things like leg length discrepancies. Some of these things have been questioned recently, and I want to kind of look into that just a little bit. So let's just back up and go over kind of some of the common things that we see and hear about that, because I know one of the most common ones is the role of the iliopsoas in producing anterior pelvic tilts. So shall we maybe go over how does that happen? How does that actually occur?

Til Luchau:

How does that happen, Whitney?

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. So when a muscle contracts, it's bringing its two ends closer together. And there's a sort of distinction often times when we look at motion in the body, especially with the extremities of what's called open chain position and closed chain position with certain movements. So an open chain position is where the distal end of a limb, or segment, is free in the air. So for example, if you're kicking a ball, that would be considered an open chain movement because your lower leg distal, and your lower leg is freely moving through the space.

Til Luchau:

Got you.

Whitney Lowe:

So the iliopsoas, when it's acting in an open chain fashion, is predominately a hip flexor and bringing the femur up towards the abdomen in hip flexion. So that's its primary function in an open chain position.

Til Luchau:

Which by the way, it's like how a quadruped uses the psoas in running. They use it to pull the leg through, pull the leg forward, to get ready for another thrust.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Now obviously, when we're standing, since we're a bipedal organism that stands on the ground, when we're standing, this is a closed chain position and you can no longer lift the distal end of that extremity up because the body weight is in contact with the ground. And at that point, the psoas has a tendency also to, as it gets hypertonic or tight or in the contraction process, pull its two ends closer together. And since the distal end is rigidly fixed to the ground, it will have a tendency to pull on its more superior end, which is the lumbar vertebra.

And so, the idea for a lot of people's biomechanical analysis is that the psoas then, in the upright position, contributes to bringing the lumbar vertebra forward in attempting more forward flexion of the lumbar vertebra. And the person may sort of react to that by attempting to kind of lean back, and that produces the increased lumbar lordosis, and a subsequent anterior pelvic tilt. So that's kind of the explanation of its potential role in that sort of postural challenge to the psoas.

Til Luchau:

Well said.

Whitney Lowe:

Dose that seem to make sense?

Til Luchau:

Well, I should say, that is the well said, classical kinesiological explanation of its action on the lumbar spine, and so then on the pelvis. There is, interestingly enough, there is a historical debate within the Rolf Institute about when Rolf world, where Ida seemed to imply that it did the opposite. That it was actually a lumbar extensor, and that its contraction would help someone flatten their lumbars.

And so, people pretty much took that on faith, and there have been some very heated debates to the point of people almost being fired and excommunicated around this very topic. But I think there's widespread agreement, that explanation that you just gave, is the conventional, kinesiological function of the psoas, although you'll hear the opposite in some schools.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. And there is some controversy too around its potential contributions to other motions, in the hip and pelvis especially, the motions of abduction and lateral and/or medial rotation. But-

Til Luchau:

Are we going there, because I mean-

Whitney Lowe:

I think we should. You had something in your book in the writing that you have about basically yeah, it might contribute to a little bit of that, but it's not worth considering because it's so minimal. So I think I'm safe, or I'm happy to leave it there at that.

Til Luchau:

Maybe the psoas is the most argued about muscle in the body. Maybe that's what it is.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

And there's so many debates about its function, and we're talking about now why you would work with the rationales where... I see that you flagged in there, "Should we even work it?" Those kind of debates are in the background. So yeah. The role, you said, of... Let's go back to the biomechanics. The role of it is thought to be, at least in most points of view, that it contracts, it pulls your pelvis anteriorly, and so that if you have a big lordosis, or have a big anterior pelvis tilt, work the psoas to help it be longer and help correct those things in course.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Yeah. And I would also say I've come across a number of times some descriptions from practitioners talking about this, ascribing certain things to it that biomechanically don't really make sense to me, and I have a difficult time sort of swallowing. Things like the psoas being a predominant contributor to a leg length discrepancy, for example.

Til Luchau:

Pulls the leg up. Sure, why not?

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Pulls the leg up. A little bit of difficulty in that when you look at physics, because it's kind of hard to pull your leg up off the ground when you're standing on it.

Til Luchau:

Every leg... Well, that's not... Most legs reach the floor, you say.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. That's right. So some of those things need a little bit more biomechanical scrutiny for us Thinking Practitioners to buy that.

Til Luchau:

Well, even some of the classical biomechanical explanations, like anterior pelvis, I'm not... You can say I'm agnostic. I don't know. Probably because there's so many debates around that, that means it's not a clear or significant effect. Or consistent effect, maybe. That's why there's so much we could argue about because it's not obvious and universal.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. And we have the potential problem of have we ever necessarily accurately demonstrated a true cause effect relationship that extends beyond just a correlation? That's an important consideration is remembering, "Well, we may have some people with what might appear to be iliopsoas tightness, and they have an anterior pelvic tilt, but do we in fact know for sure that that's what caused it? We're still not quite there.

Til Luchau:

Yeah.

Whitney Lowe:

There was a great... I saw this a couple years ago. I'd love to remember where I saw this. Discussion of learning how to make the distinction between causation and correlation.

Til Luchau:

Yeah?

Whitney Lowe:

Because a lot of times, two things will occur together, but that doesn't mean they necessarily caused each other. They did this study where they would graph the occurrence of two particular items on a graph, and see when did those two things overlap, and have a graph that looked very similar. And there was something like a really clear exactly correlation between people born in September and people that were killed by donkeys, or something like that.

Til Luchau:

When's your birthday?

Whitney Lowe:

My birthday is in December.

Til Luchau:

Okay, you're safe. You're good.

Whitney Lowe:

I'm safe. Yeah.

Til Luchau:

Me too.

Whitney Lowe:

So I'm good. But anyway, just keeping in mind that a lot of times we may see some of these related things throughout the body, but that doesn't necessarily mean that there is a cause effect relationship there.

Til Luchau:

Or that even just because a muscle, like you said, does contract and pull its two ends closer together, that if the two ends are closer together, that muscle is tight and needs to be lengthened.

Whitney Lowe:

Right.

Til Luchau:

Yeah.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

All right. So you were saying leg length discrepancy, maybe that's not so plausible?

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

Any other structural challenges you want to bring in there? I got one, by the way.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

I'm thinking of scoliosis where if you look at an anatomical picture, it's pretty easy to imagine how one side of one psoas, they being tighter because it pulls the lumbars into a curve that the other side wouldn't be able to balance. So for a long time, actually... So it looked so obvious, that for a long time, that standard treatment of idiopathic adolescent scoliosis was to sever the psoas down at the front of the hip. Surgically cut it apart.

Whitney Lowe:

I saw you had said something about that in one of your articles. I thought it was fascinating. I hadn't ever heard that before. And so that seems to me a pretty extreme kind of attempt to address that.

Til Luchau:

And it's one of those cases of causation versus correlation, because when finally someone did a prospective study to see if people were different after the surgery, there was no average improvement of people between... And maybe worse that had one psoas cut. So that fell out of favor in the '50s. But up until that point, yeah, that was thought to be, "Oh, look at that. That muscle is short. Let's cut it. That's going to make the scoliosis better." It didn't. It didn't vary.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Right. Well, that does reflect what was so much the dominant sort of mechanistic model during that time period for all kinds of things of looking at the body predominately as a machine that just we could cut things, screw things in, just plug things in and the mechanics would be very much like a piece of machinery. We of course now know that doesn't often work the same way.

Til Luchau:

Yeah.

Whitney Lowe:

But back to your thing about scoliosis, looking at that and sort of expanding that idea, scoliosis, I mean the psoas is many times blamed for all kinds of contributions to other types of back pain problems. So what are your sort of thoughts, ideas about the role of the psoas in back pain?

Til Luchau:

Yeah. Myself, I'm of two minds. One is that no, I don't think the psoas is necessarily a consistent cause of people's back pain. I think it may be in some cases. And the studies around that... I'm just pulling this up from memory, and I can pull up a reference and put it in the show notes. But studies of, let's say psoas strength, or psoas... Maybe it's cross-section I think is what it was. Psoas cross-sectional size in people with back pain, was no different on average. There were a few cases in this study of people with really severe back pain having smaller psoas, but that's not an established correlation or cause at all. It could be that they hurt so much they didn't move and their psoas got smaller.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

So, the correlation has not been clearly demonstrated in a research fashion at all. In fact, the research suggests maybe it's not a significant contributor you could say.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

So that's the first mind. The second mind I have is that I've had experiences with my own body, and working with clients, where the right kind of work with the psoas helps the back feel a whole lot better. That's pretty clear empirical evidence, maybe. Experiencing my own limited sense. So there's times when some good work with the psoas can really help a backache or back pain, for sure.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. And so let me just pose the question that of course I think might depend on what the nature of that complaint was to begin with.

Til Luchau:

Absolutely.

Whitney Lowe:

What do you think is the... I hesitate to use the word mechanism, but what do you suppose the rationale behind the success might be in those instances?

Til Luchau:

Yeah. I mean, back then I thought... I'm thinking of one of my first serious disasters in my practice room where it was a whole disaster of a session. The woman was in a lot of pain. She couldn't get childcare. She showed up with her baby. I tried to help her. The baby's crying too in the room. We're trying to work on her. I'd been out of school maybe a year or two. And it seemed to be helping. It seemed to be feeling better, in spite of the baby crying, everything else going on. But then when she tried to get up, her back just seized up. She just was in such pain.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

And I think I even had another client coming or something. I remember some time pressure on the situation too. So and I don't even know where I got the idea to try this, but I thought, "Okay. Let's just try your psoas gently." And so I tried her psoas gently. And lo and behold, that was the silver bullet, in that case. She pranced out, the baby is giggling, and everyone lived happily ever after in that case. And at that time, I thought, "Okay, so this is... I'm pushing the lumbars back." Or, "I'm releasing the psoas to balance it out." Those models that I was trained in. Anymore, I don't know. I mean, I can think it's just as plausible to think that the intense, focused, careful, slow experience of having your psoas gently worked could be resetting two little [inaudible 00:21:59] response, for goodness sake. I don't know.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

Maybe there's some other factors at work there too.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. I would think that that certainly makes a great deal of sense, especially the more we kind of sort of understand the mechanics of what we are doing. We'll get into this a little bit more detail here in a few minutes of what actually happens in the many different approaches where we do attempt to do that. So you've mentioned some in your article, and I know this has been a fair amount of controversy. We talked about this both within the field at large, our field and others as well, about there's all this controversy around the iliopsoas, and should we even attempt to do work on it, because there is a lot of concerns about the sensitivity of structures in the area, some other things around there. So what are your current thoughts about that? Do you still advocate doing this a good bit, or what kind of situations do you find most beneficial in doing that?

Til Luchau:

Yeah. I'm way more cautious than I used to be. I still I'm happy to have the chapter about psoas work in my book, and I'm going to include that in the handout, and I'm still talking about it. I have been the target of some criticism for that. And in fact, there was one of our competitors, who shall remain nameless, took this chapter, when it was published as an article, and took excerpts, and then substituted other people's images from the internet of doing some fairly brutal psoas work and saying, "Here. This is why people should not be teaching psoas work." I thought that was kind of intense.

The point of my whole article was we got to be really careful. Maybe there's some times, and here's 100 ways to be careful. He took one or two statements out of context in there, and took other people's illustrations to say, "This was brutal." And again, the concern... Yeah, I know. The concerns are valid. And still, I mean now and then will surface. Someone will send me and say, "Til, did you know that you're teaching something that... " "Here. Let me send you the article so you can read the whole context."

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

It's, let's say, with a lot of caution. Yes. I think in the right... With someone with skill, and the right kind of rapport, and the right kind of circumstances, the right kind of resilience in the client, because it's not for every client either then, sure there can be times when this can be useful. Should we be cautious? Absolutely. And I'm certainly cautious now about even talking about psoas work after that.

Whitney Lowe:

I don't doubt that. Yeah. Making me think that maybe we need a podcast episode on digital piracy and ways in which your work can be sort of taken out of [crosstalk 00:24:44] misinterpreted, because I certainly think we've both had that happen to us at different times here.

Til Luchau:

Okay. What do you think? You got any thoughts on that? Should we be attempting to work it?

Whitney Lowe:

I do. And I have really changed my tune a lot of psoas work a great deal over the years, and especially in recent years for a number of different reasons. For me, a lot of this began after some discussions with a number of people who were doing significant cadaver dissections, and talking about the incidence of undiagnosed aortic aneurysms they were finding in cadaver dissections.

And I was reviewing a lot of the anatomy around what we're doing in the iliopsoas region, and recognizing that in terms of people talking about cautions, they often talk about the aorta or the superior vena cava as precautions, but you don't hear many people talking often about the external iliac artery and external iliac vein, which are the branches that come off of those major circulatory structures that lie almost directly over the top of the iliopsoas.

And when people advocate techniques of getting in there and pressing on the iliopsoas, remembering that you are pressing through lots of different tissue layers before you contact that, it does seem feasible that in instances, you could put pressure on those circulatory structures and cause a backflow of pressure in there, and possibly cause a bursting of those aneurysms. And that has been reported to have occurred before, at least to a suspicion about that.

Til Luchau:

Oh, as a result of psoas work?

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

Wow.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Yeah.

Til Luchau:

Okay. Because having one thing... I want to hear more, but because one of the things I did when I published that chapter was spent a couple days doing as in-depth research as I could for reports of casualties or injuries resulting from psoas work, and could find very little. In fact, only found one at that time. This was five years ago.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

But no, I think the potential is definitely there, and I think that mechanism you described is plausible, and certainly should be considered.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Yeah. And this gets back to... And I know you had said that in your article. This is something that I wanted to bring up because I think it's an important thing for us to consider, because this is an issue obviously not only in the iliopsoas work and the iliopsoas region, but this is for all over the body when we talk about the potential problems that may occur with certain types of treatments. We don't really have a good reporting mechanism to report these kinds of issues. And so often-

Til Luchau:

We got Facebook.

Whitney Lowe:

Oh, okay. I forgot about Facebook. Yeah. Okay. Twitter. People can tweet their-

Til Luchau:

No, you're right. Point well taken. In fact, that's the only case I found was somebody's repeating a case they had heard about on Facebook. But anyway.

Whitney Lowe:

And the reason that I bring that up is that... And again, I'm going to say this is anecdotal, but it gives me pause to think that I'm not the only one where this has occurred is that quite often, for me in practice, I have had clients come to me and tell me they were hurt by somebody who did something too aggressive to them previously. And I asked, "What did you do about it?" They said, "Nothing. What do I do?"

And there really isn't a reporting process to report those kinds of things. And this is another part of... There's this whole, long other story of why I have always been very deeply involved in the credentialing world, because I think some of these aspects of the importance of being able to document the potential problems that may occur from inappropriately applied treatments, we don't have a good mechanism to report that and get that kind of information out. So I think it occurs a lot more often than we're aware of.

Til Luchau:

Now you're making me think. And it's the old adage, "An absence of evidence is not evidence of absence."

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

So just because I couldn't find any stories of people reporting injury or problems from psoas doesn't mean it doesn't exist. Point well taken. I think we should scratch this whole episode right now. Let's just take it.

Whitney Lowe:

All right.

Til Luchau:

No. But it does bring up the question of, "How do we as practitioners, as teachers, as podcasters talk about this responsibly?" So I think I'm going to give you my working hypothesis. I think I'm going to continue to talk about it, and I'm going to really emphasize the cautions. And I think like you're doing, really emphasize the potential for harm there so as people use that work they were trained in, or maybe go learn more work, they're really aware of how and when and how not to work it.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. The other thing that really began to bother me about the traditional approaches to the iliopsoas work that most of us learned, most of us practiced for many years... I certainly did do it this way. The idea of placing your fingertips gently on the abdomen and sort of working your way down through their... There is usually a discussion about you just move your fingers through there, and then all the underlying mesentery and everything gets out of the way so you can contact the iliopsoas.

And I started looking at this like saying, "How does that work? Do the intestines, all those multiple layers of soft tissues under there just say, 'Oh, here comes those fingers for iliopsoas. Let's get out of the way.'" Because if you look at an actual abdomen and dissection, there's not much room there for that stuff to actually get out of the way. And so what that means is when we contact the iliopsoas to do work, we are pinning the intestines against that muscle. And those tissues probably won't have an issue with that in most cases, but-

Til Luchau:

If you're nice.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah, if you're nice.

Til Luchau:

And they're healthy, etc., etc. But yeah.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. If you're overly aggressive or there is a condition that you're maybe not so aware of, like Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome or something where a person has connective tissues weakness, you could potentially cause some damage to those softer connective tissue structures that aren't meant to take that kind of pressure. So that's a caution that, to me, doesn't get talked about as often.

And if you think about the biomechanics of our work in attempting to treat the iliopsoas that way, when you contact the abdomen, and you're pressing through skin, subcutaneous fat, facial layers, abdominal obliques and all that kind of stuff, that stuff is all... It's like a big... It's like four layers of blankets, and you're pressing on it, and then somehow or another, you're giving a specific contact to a tissue way down under there with all this other stuff bending in between your fingers.

So, you have a lot of stuff on there that's muffling your palpatory sensitivity and your capability to really get there. So those were a lot of the things that made me really question what I was doing there and ask the question, "Hey, maybe is there some other way to do this that might get beneficial results without these potential challenges or potential dangers there?"

Til Luchau:

All right. So I'm just bookmarking there's two things in that sentence I want to hear more about. One is the other ways, of course. The other is 'this'. Doing what? What is it that we're trying to accomplish?

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Yeah. So, the 'this' is the mystery that we talked about earlier of attempting to, and I'm going to put this in air quote, "work the iliopsoas," whatever that means. Or the common term that we hear in our field about releasing the iliopsoas. What does that really mean? What does the release mean? I think in most situations, we consider that something where there is an apparent palpatory decrease in hypertonicity of the muscle, and we say, "It has released." And that is, in many instances, our goal.

But if you take things like postural challenge, like we were talking before, like the anterior pelvic tilt, and the exaggerated lumbar lordosis, I certainly think after looking at this for a lot of people, a lot of years, a lot of attempts to do this, just working the muscle alone may give some short term changes in proprioceptive awareness, and might make some improvements, but it's unlikely to produce a lasting postural change alone, just with what we're doing with our manual therapy work. So it can be a piece of the puzzle, and it can certainly help people with certain pain complaints, but I don't think that we're going to get in there, work somebody's iliopsoas, and magically permanently change postural challenges like that.

Til Luchau:

All right. So now you've brought up permanent postural change. That's going to have to... That's a huge discussion. It goes to the question, "Do we do that anywhere? Is there any magic muscle or magic structure that does that?" Who knows. But anyway, back to you point, yeah. I'm with you. I agree, by the way.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. So anyway, I don't want to say there's not benefit in it, because I think there can be benefit in working with this. And so I began focusing a lot more attention on some things like muscle energy technique methods, resistance stretching, something that Jules Mitchell talks a lot about in her book that we addressed earlier in our stretching episode [crosstalk 00:34:31]. Yoga Biomechanics is the book, and she mentions in there resistance stretching, which I've been playing around with a lot recently, getting some really beneficial results.

And essentially what that is, is it's taking a muscle near its end range, and then putting an eccentric load on that muscle, and gradually lengthening it to its full length against some sort of eccentric resistance, and doing that repeatedly, and relatively quickly over the course of just a few seconds. This will look a lot like for anybody who studied the work of Aaron Mattes and his active assisted stretching methods, that sort of process. Relatively short stretches near the end range of motion using some eccentric engagements.

And I've found that to be really helpful in addressing what appears to be iliopsoas tightness. If you do an evaluation procedure like the Thomas Test, which is a common orthopedic test that's used to evaluate iliopsoas tightness, and you can see some significant changes. [crosstalk 00:35:34] Right. Yup. Yeah. And Til, maybe remind me after we're done, and we'll put that link to the Thomas test in our handout as well for everybody.

Til Luchau:

I got to note it right here. That's a good one.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Yeah. So that's kind of where I am with it is trying to find some ways that are not potentially invasive to run up against some of these anatomical challenges, but the other thing is it just feels really weird for a lot of people to have you digging deep into their abdomen, and it can be more comfortable, and possibly less uncomfortable for the client to try some of these other strategies as well.

Til Luchau:

Yeah. That's a big factor. That's a big factor. The comfort factor you're naming. And I like the alternatives you're presenting there to hands-on direct pressure work. I'm thinking of Paul Ingram's Psoas, So What? article from about five, six years back. Like a lot of his stuff, it's fun if you don't mind a little hyperbole. He does a really great... He's very thorough as a writer, and I always enjoy the points he brings out. But his Psoas, So What? gives the critiques against those kind of things, a big one being, "It hurts," he says. People don't like it.

Now I would say it shouldn't, it doesn't have to, and that's not a sign of success. In fact, I'll say very quickly, you shouldn't be scraping, digging, poking, prodding, or massaging even, the psoas. You'll see the technique that I'm going to describe, and then I'll put that chapter in the handout and such. I'll go ahead and put a link into the video of that technique, too. It's a waiting, it's a sinking, it's a listening technique with pressure secondary.

And my own shift has... I'm sorry. My own goal has shifted to this question, and you're like, "How do we do this to the psoas?" My goal has shifted from a mechanical effect in the psoas to, like you said, a proprioceptive effect on the psoas. The psoas is super sensitive. Liz Koch, for all the things she says, one of the things she says is, "You can think of it like the tongue. It's a long muscle that's super sensitive, highly integrated," so that's an interesting analogy.

And we wouldn't get our elbow in there on someone's tongue, I don't think. We wouldn't be poking around on the tongue. But even, like you said, it's below half a dozen or so very delicate layers of structure. So as we're working through those things, it's more about a sensory and a sensing experience than a mechanical differentiation. And there's good reasons... I think I'm drifting now into like, "What do we need to be careful of?"

There are reasons to not scrape, or slide, or move in there. Like the various arterial structures you named, as well as ureters, which run parallel to the psoas on their anterior surface. And there are concerns, I know in visceral work about strumming the psoas, and there's stories about people, they're anecdotal as far as I know, displacing the ureter with that kind of aggressive psoas work. And whether its bruising or displacing, I don't know, but there's yeah, something to be cautious of for sure.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. And one thing we haven't mentioned here too, and this was in your article, in talking about the anatomical structures and the anatomical relationships. There's quite a number of nerves very close, adjacent to, and in many instances also perforating the psoas [crosstalk 00:39:14] on those tissues might affect neurological symptoms as well.

Til Luchau:

Beneficially or adversely. The nerve trunk [inaudible 00:39:24] pass through the belly of the psoas between those layers you talked about. So yeah. Sure. Maybe there's a plausible rationale for including psoas relaxation or awareness in your work when there are neurological symptoms like sciatic pain, or femoral nerve pain. But there's also the potential, if you're in there being rough, that you could irritate, say, the abdominal plexus. You're working through the place in the body that has more neurons than any other part of the body except for the brain. Your gut has more neurons than anything but your brain. Like you said, you're working through that. You're probably, in spite of our old rationales, we're probably not working around it all. We probably are pressing it up against the spine.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

So it's like having a tongue through the brain, pressing the brain up through the tongue. That's what we're doing there.

Whitney Lowe:

I liked your analogy earlier of the elbow work on the tongue, and I was trying to visualize like maybe a... Maybe that can be a new cathartic therapy of some kind for-

Til Luchau:

Well, I mean we should say, "Yeah, that that catharsis piece is part of the psoas tradition too, way back through Wilhelm Reich, who would deeply massage people's belly to get their emotional armor broken down in his model, and people have emotional releases." That's like, "It's intense." That intestine of your belly work, but there is a role in contracting and tightening there as a way to manage emotion, expressing emotion.

Whitney Lowe:

Of course. And I mean, you see this throughout the animal kingdom of the necessary evolutionary essential necessity, basically, of protecting the abdomen. That's just a primal reflex in our neurological system, and I think that kind of goes a lot into what many of the body oriented psychotherapy practitioners focus on and emphasize with the crucial role of abdominal contractures being associated with so much sort of emotional energy in many instances.

Til Luchau:

Yeah. Or like TRE, which works to fatigue or stress the psoas. You get some trembling, and people have often emotional experience, or it resolves kind of activation. Just models there, using the psoas again.

Whitney Lowe:

Right.

Til Luchau:

Any more contraindications? We're not going to be able to do a complete list. I think we should just acknowledge that. But any more that you want to mention?

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Those are the biggies for me was mainly the proximity of circulatory structures, and the fact that we're pressing directly onto so many abdominal viscera and basically pinning against the muscle.

Til Luchau:

Yeah.

Whitney Lowe:

Even I really believe... I know some people advocate moving into a side lying position and then saying, "Well, the viscera will then move away from it." But the viscera moving toward the spine, and that's right where the muscle is. So I still think you're going to be... There's just not enough room in there for everything to move away to the side. I remember when I was first taught this psoas work, our teacher basically gave us this visualization of just take your fingers and just kind of wave them through there, and that sort of parts the seas of your viscera getting out of the way. It'd be great if it really worked. I could think of a lot of places in the body where that could be really helpful, but-

Til Luchau:

Just admit it. We're pushing on the viscera.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

Straight up against the gut. Yeah, you're right. I [inaudible 00:42:54] nice analogies. Stacey Mills, one of my early Rolfing teachers said, "Imagine that you're feeling around and a mud puddle for broken glass. So you're going to be that slow and that careful with your own fingers not to use any pressure, not to do anything sharp or hard. There should be none of that sensation, of course." Another standard safety caution is don't work above the abdomen. That getting up into the renal arteries, the arteries that are in the upper end of the psoas where go out to the kidneys. So that's kind of the classic no-go zone.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah.

Til Luchau:

But all of this... And if a big thumping thing you feel there, that's the aorta, rather, and it's not meant to be massaged. In fact, Robert Schliep, one thing he said is, "The only time that the organism, the animal, is used to having tactile sensation on the psoas is when they're being eaten by a predator. That means they've been eviscerated already, and they automatically go into a state of like, 'I'm in trouble with this situation.'"

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. Right. Yeah. So well, I think we have addressed quite a number of pieces of this controversy of the iliopsoas. Anything else that you want to spin in there before we wrap up on that for today?

Til Luchau:

I just want to say that it was a rite of passage for me. Not in its intensity. I got to say, I think I was 19 when I got Rolfed the first time and had my psoas worked on, and in that Rolf sequence, it was kind of a build up to that session where that happens, and it was a sort of passage, and it wasn't intense in like a rough way at all. He was very delicate. But to feel that sensation of the legs connected to my spine was a kind of revelation. I think I still... I was impacted by that enough that that's still what I look to bring to my clients when I decide that it's appropriate and all these cautions have been followed. Just that sense that, "Wow. My legs are actually connected to my spine. That's a new revelation."

Whitney Lowe:

I think too, and we've touched on this in a number of different topics, of just really talking about in terms of our goals of treatment oftentimes seem to, at least this is true for me and I think you've said similar things too, that oftentimes our goals of treatment focus a great deal more on proprioceptive awareness. And I have had a lot of similar kinds of sensations of things like, "Oh, wow. That is really wild to feel that," and knowing something about anatomy of where some things are connected or brought together. But for the person who's sort of experiencing some of those things in their body, that can be a real fascinating kind of revelation. And increased proprioceptive awareness can have all kinds of potential benefits.

Til Luchau:

That's great. Yeah.

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. A number of different ways to get there.

Til Luchau:

Well, wrap up time you think?

Whitney Lowe:

Yeah. So I will call that a wrap on this discussion for today, and maybe some other good questions or comments will come out of that of things that we want to address with other people going down the road afterwards. So we would like to today thank ABMP, who's a proud sponsor of The Thinking Practitioner podcast. Note, all massage therapists and body workers can access free ABMP resources and information on the coronavirus and the massage profession at abmp.com/covid19 including sample release forms, PPE guides, and a special issue of Massage & Bodywork magazine where Til and I are frequent contributors. And for more, check out the ABMP podcast available at abmp.com/podcast, or wherever you prefer to listen.

Til Luchau:

Yep. Thanks to them and to our other sponsors. Come on by our websites for that handout we mentioned. I'm going to put the link in the show notes, so it's going to be there in both of our websites too. You can also get a transcript of the episode, and there's a bunch of extras there. What's your site, Whitney?

Whitney Lowe:

They can also find stuff from us over at academyofclinicalmassage.com. And Til, where can they find out more about you as well?

Til Luchau:

Our site advanced/trainings.com. Advanced/trainings.com. Email us about questions or topics, things you'd like to hear about. Your complaints about us broadcasting about the psoas, your congratulations, whatever you want to send us, we'd love to hear about it. The email to reach both of us info@thethinkingpractitioner.com, or look for us individually on social media. I'm at @TilLuchau. How about you, Whitney?

Whitney Lowe:

And I'm also there at @whitlowe. I can be found there. And you can also follow us on Spotify, or rate us on Apple Podcast, or wherever else you happen to be listening to your podcast. If it's a Walkman or whatever else your device is that you're doing these days. So thanks very much. Also to all of our listeners, we really appreciate your hanging around with us. Tell a friend, share the news, and let us know what else you'd like to hear about. So Til, great talking about this today, and I'll look forward to chatting with you some more again in a couple weeks.

Til Luchau:

Thank you, Whitney. I'm going to dig out my tin can and a string and see if I can hear the podcast over that. Thanks for the conversation today.

Whitney Lowe:

You bet. Sounds good we'll talk again soon.

Live Workshop Schedule

Stay Up to Date

...with the Latest Episode, News & Updates

Get our free Techniques e-Letter

You'll occasionally receive the latest schedule updates, tips, secrets, offers, resources, and more.

Check out our ironclad privacy and SMS policies. You can unsubscribe/stop at any time.

This Month's

Free Online Course

Our gift to you.

Includes CE, Certificate, and Extras.

Follow Us

Join us on FaceBook, Instagram, Twitter and YouTube

for information, resources, videos, and upcoming courses!

0 Comments